The second-largest city in Poland and one of the country’s most important cultural and tourist centers.

I once came across a post on Twitter that said something like:

“I’m in Budapest! It’s amazing here! Kraków doesn’t even compare!”

Along with a few nice photos of the Hungarian Parliament, Margaret Bridge, and so on.

It had never occurred to me to compare these two very different cities, but that tweet made me reflect.

Is Budapest better?

While Budapest is undoubtedly an impressive city, claiming that “Kraków doesn’t even compare” is not only exaggerated but overlooks many key aspects that make Kraków one of the most attractive cities in Central Europe.

Sure, the Hungarian capital boasts the monumental Parliament on the Danube, elegant bridges, Art Nouveau architecture, and famous thermal baths.

But tourism is not just about “pretty pictures” — it’s also about atmosphere, walkability, historical cohesion, and urban storytelling.

In these respects, Kraków clearly outshines Budapest. Here’s why:

A compact and vibrant city center

Kraków has the largest medieval market square in Europe — not only the city’s showcase but also the beating heart of its nightlife and culture.

Within just a few hundred meters, you’ll find the Cloth Hall, St. Mary’s Basilica, the Town Hall Tower, and just beyond: Kazimierz, the Planty Park, Wawel Hill, and even the Vistula boulevards.

This is a city you can explore entirely on foot, constantly stumbling upon something interesting.

In Budapest, many attractions are more spread out. The Royal Castle is located in Buda, the quieter, more residential side of the city. Pest’s center feels more “imperial” but has less of that lively urban fabric that invites you to wander.

Unbroken historical continuity

Unlike Budapest, Kraków was largely spared during World War II. As a result, it preserved its layered urban structure — from Romanesque cellars to Gothic churches, Renaissance townhouses, and Baroque palaces.

Walking through Kraków, you feel history — not just the monumental kind, but also the everyday life of past centuries.

Budapest, by contrast, suffered significant destruction during WWII and the Hungarian Uprising of 1956. Though grandly rebuilt, many parts of the city lack authenticity.

Atmosphere — something no photo can capture

Kraków has a unique aura — the city of kings, poets, artists, and students.

It’s rich in events, festivals, clubs, intimate theaters, and art galleries.

The Main Square and Kazimierz are alive year-round. Even lesser-known districts like Podgórze or Kleparz have their own character and stories.

Budapest certainly has nightlife (notably the so-called ruin pubs), but lacks a single central area of activity like Kraków’s Main Square.

Many visitors also remark that the city feels more spread out and less pedestrian-friendly at night.

Kraków as a base for exploration

Another advantage of Kraków is its proximity to other important destinations:

Wieliczka Salt Mine, Ojcowski National Park, the Benedictine Abbey in Tyniec, Nowa Huta, and even Zakopane in the mountains — all within 1–2 hours.

Kraków isn’t just a destination — it’s a perfect base for wider exploration.

Let the Hungarians speak

Hungarians — a nation traditionally attached to their own heritage — visit Kraków in large numbers, treating it as a special place.

This isn’t just about tourist appeal. For many Hungarians, Kraków holds deep cultural and historical meaning.

Hungary’s intellectual and political elite studied for centuries at the Jagiellonian University — among its alumni are Hungarian kings, diplomats, writers, and scholars.

In Hungarian literature, Kraków often appears as a “gateway to the north” — a place of encounter with another world, but also with their own heritage.

It’s no coincidence that so many Hungarians choose Kraków for a city break.

That speaks volumes.

It is one of the oldest and most significant cities in Poland, rich in history, culture, and art.

Kraków is known for its many important landmarks, such as Wawel – the royal castle with a cathedral on the hill, the Cloth Hall (Sukiennice) – a medieval market hall, St. Mary's Basilica – one of the largest and most impressive Gothic churches in Poland, and the Old Town – a historic district full of townhouses, churches, and museums.

Kraków`s Old Town

The focal point of the Old Town is the Main Market Square — one of the largest town squares in Europe. It is home to numerous landmarks such as the Cloth Hall (Sukiennice), St. Mary’s Basilica, and the Town Hall Tower.

The area surrounding the square is filled with charming streets, historic townhouses, cafés, restaurants, shops, and other attractions that draw visitors from all over the world.

The Town Hall Tower

The Town Hall Tower, located on the Main Market Square in Kraków, is one of the city's most iconic landmarks and the only remaining part of the former Kraków Town Hall, which was demolished in the early 19th century.

The tower was built during a time when Kraków was flourishing as the principal city of the Kingdom of Poland. It was part of a larger complex that housed the municipal government.

In 1820, the Austrians ordered the demolition of the town hall as part of a campaign to “tidy up” the market square — only the tower was left standing. This was part of a broader process of urban “rationalization” typical of 19th-century partition-era administrations.

Today, the interior houses a branch of the Museum of Kraków. Visitors can explore exhibits on the history of the tower, medieval clock mechanisms, and the city’s historic administration.

Wawel

The Royal Castle on Wawel Hill is one of the most important historical landmarks in Poland. Built in the 13th century, it served as the royal residence for many centuries. The castle houses numerous state rooms, including the Senate Hall, the Deputies’ Hall, and the Grand Hall, as well as museum collections such as the Armory and the Royal Apartments.

Also located on Wawel Hill is Wawel Cathedral, one of Poland’s most significant churches. It is the seat of the Archbishop of Kraków and serves as the burial place of many Polish kings and national heroes, including Jan III Sobieski and Tadeusz Kościuszko.

Wawel is not only one of Poland’s most important monuments but also a key site in Kraków. It holds deep significance for Polish history and serves as a vital center of culture and art.

The Sigismund Bell

The Sigismund Bell (Dzwon Zygmunt, also known as the Zygmunt Bell) is one of the most famous bells in Poland — and even in all of Europe. It hangs in the Sigismund Tower of Wawel Cathedral in Kraków.

It was commissioned by King Sigismund I the Old as a symbol of the power of the Jagiellonian dynasty and Polish statehood. From the beginning, it was intended for Wawel Cathedral, and it was placed in a specially built tower — the Sigismund Tower.

The bell rang for the first time on July 13, 1521. From the start, it was used to mark major religious and state occasions — a tradition that continues to this day.

The Sigismund Bell tolls only on exceptional occasions, such as:

- the death or election of a pope,

- the death of the president or other national figures,

- national and church holidays (e.g., May 3rd, November 11th, Christmas),

- the installation of the Archbishop of Kraków,

- important historical anniversaries (e.g., the restoration of independence).

St. Mary`s Basilica

St. Mary’s Basilica in Kraków is one of the most important and recognizable churches in Poland. Its asymmetrical towers, stained glass windows, the altar by Veit Stoss, and its role in Kraków’s cultural and spiritual life make it a true Gothic gem — not only architecturally, but also spiritually, historically, and symbolically.

The current structure dates back to the 14th century and was built following destruction caused by Mongol invasions (1241). From its inception, the church served as Kraków’s parish church, primarily for the townspeople — unlike Wawel Cathedral, which served the royal court and high clergy.

The Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary stands in the northeastern corner of Kraków’s Main Market Square. It is oriented, meaning its main altar (the presbytery) faces east — in line with Christian tradition (symbolizing resurrection, light, and Christ as the rising sun). This means the church’s façade and towers face west — toward the square, though not aligned exactly with its axis.

The church predates the present-day Market Square, most likely having been founded in the 12th or early 13th century on the site of an earlier temple. When Prince Bolesław the Chaste granted Kraków its city charter under Magdeburg Law in 1257 and laid out the regular grid of the Main Square, the pre-existing church was preserved.

According to legend, the two towers were built by two brothers. When the younger brother saw that the older was constructing a taller tower, he killed him out of jealousy. Stricken with guilt, he later threw himself from the tower, holding the knife used in the murder. That very knife can still be seen hanging on the wall of the Cloth Hall (Sukiennice) — on the church-facing side.

Of course, it's just a legend — but one that beautifully illustrates the spirit of urban folklore.

Veit Stoss Altar in St. Mary`s Basilica

The largest Gothic altarpiece of its kind in Europe — over 13 meters high and 11 meters wide.

Created between 1477 and 1489 by Veit Stoss (Wit Stwosz), a master sculptor from Nuremberg. The altarpiece depicts scenes from the lives of Mary and Jesus: the Dormition, Assumption, and Coronation of Mary, as well as episodes from the Passion and the childhood of Christ. The figures are carved from linden wood, then polychromed and gilded.

During World War II, the altar was dismantled and hidden by the Germans — it was taken all the way to Nuremberg. It was recovered and brought back to Kraków after the war.

The Cloth Hall (Sukiennice)

The origins of the Cloth Hall date back to the times of medieval trade, even before the city was officially chartered in 1257. At that time, two rows of wooden cloth stalls stood in the market square — where merchants traded one of the most valuable commodities of the Middle Ages: cloth. These stalls were aligned east–west between the present-day St. Mary’s Basilica and the Town Hall Tower.

Under the reign of King Casimir the Great, after several fires and destructions, the wooden stalls were replaced by a permanent masonry building. This first stone-and-brick Cloth Hall featured a central aisle with rows of shops on both sides. It was built in the Gothic style and topped with a high gable roof. The central passage remained open, and merchants from Poland, Hungary, Germany, and Italy traded cloth, silk, furs, spices, gold, and silver inside.

By the 19th century, the Cloth Hall on Kraków’s Main Square had fallen into serious disrepair. There were real plans to demolish it entirely. Fortunately, thanks to the efforts of Kraków’s intellectual and artistic elite — including Jan Matejko — the idea was abandoned in favor of renovation and rebuilding.

Major renovation: 1875–1879

The redesign was planned by the young architect Tomasz Pryliński, with supervision by Prof. Władysław Łuszczkiewicz, a renowned art historian and mentor to Matejko.

Annexes were removed, arcades were reopened, and Renaissance-inspired gargoyles (mascarons) were added to the attic. The upper floor became home to the first permanent branch of the National Museum in Kraków, opened in 1883, featuring works by Matejko, Siemiradzki, Malczewski, and others.

Franciscan Basilica in Kraków

The Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi in Kraków (commonly known as the Franciscan Church) is one of the oldest and most unique churches in the city. It blends deep Franciscan spirituality, Gothic architecture, and exceptional Art Nouveau art, especially through the work of Stanisław Wyspiański.

The church was founded by Prince Bolesław the Chaste and his wife Saint Kinga, following the arrival of the Franciscans in Kraków. Construction began around 1237. It is one of the first brick churches in the city — earlier temples were mostly wooden.

The most famous works in the basilica include:

“God the Father – Let It Be”, a monumental stained-glass window above the entrance, considered the greatest Art Nouveau stained-glass piece in Poland.

Other stained-glass windows feature depictions of saints, the creation of the world, symbols of nature and light — full of expression and mysticism.

According to monastic tradition and historical chronicles, Władysław the Elbow-high is said to have hidden in the Franciscan monastery during one of the periods of exile and persecution in Lesser Poland — likely around 1290–1300, when Kraków was taken over by supporters of Wenceslaus II.

Teatr im. Juliusza Słowackiego w Krakowie

The Juliusz Słowacki Theatre in Kraków is one of the most beautiful and important theatres in Poland, often compared to the Paris Opera or Vienna’s Burgtheater. It is a jewel of Kraków’s theatrical architecture and served for decades as the heart of the city’s artistic life, especially during the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) period.

It was built on the site of the demolished Church and Hospital of the Holy Spirit, a decision that sparked considerable controversy at the time.

The design was inspired by Charles Garnier’s Paris Opera House.

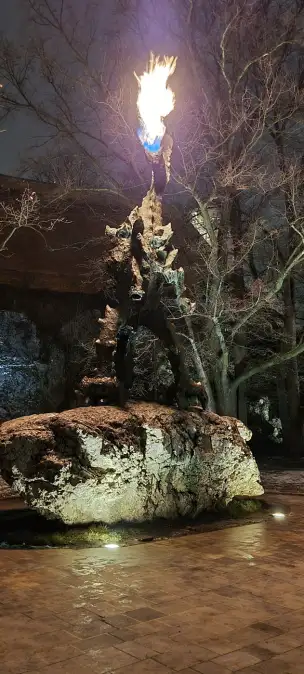

The Wawel Dragon

The Wawel Dragon is Kraków’s most famous legend — a symbol of the city, the hero of fairy tales, monuments, and even a fire-breathing sculpture located beneath Wawel Hill.

The oldest version of the legend appears in the Chronica Polonorum by Wincenty Kadłubek (13th century). Kadłubek described a dragon living at the foot of Wawel Hill that terrorized the area, devoured cattle, and demanded human sacrifices — mainly young girls.

In the most popular later version (recorded by Jan Długosz and others), the dragon was defeated not by force, but by trickery. A poor but clever shoemaker named Dratewka stuffed a sheepskin with sulfur and tar, then offered it to the dragon as a “sacrificial lamb.” The dragon ate it, then drank so much water from the Vistula River that it burst.

The story may echo ancient myths about creatures guarding the entrances to caves or the underworld — common across European folklore. Wawel, a former pagan stronghold and sacred site, does indeed have its own natural cave: the Dragon’s Den (Smocza Jama), which still exists beneath the castle.

The Wawel Dragon sculpture, created in 1972 by sculptor Bronisław Chromy, a Kraków artist and professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, stands at the entrance to the Dragon’s Den on the river side of Wawel Hill.

The sculpture is powered by natural gas and is designed to breathe fire. Originally, the fire-breathing occurred every few minutes — today, it can be activated by sending an SMS (the number is posted on a plaque near the statue).

Church of St. Adalbert (Święty Wojciech)

The Church of St. Adalbert on Kraków’s Main Market Square is one of the oldest and most fascinating landmarks in the city — modest in appearance, yet incredibly rich in history and symbolism.

According to tradition, St. Adalbert (Święty Wojciech) preached at this very spot in the late 10th century, before his missionary journey to Prussia and martyrdom. The first chapel, likely made of wood or stone, may have been erected here as early as the 11th century.

The current church was built around the 11th–12th century in the Romanesque style, which is evident in its thick walls and small windows.

Though often overlooked by tourists focused on the Cloth Hall or St. Mary’s Basilica, the Church of St. Adalbert stands as one of the oldest and most significant witnesses to Kraków’s history — dating back to a time before the city took its current form.

Piwnica pod Baranami

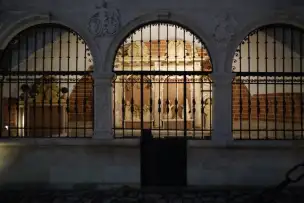

Piwnica pod Baranami is a true Kraków legend — one of the most important places in postwar Polish culture, both artistically and socially. It operates in Gothic cellars dating from the 15th–16th centuries, which once housed a tavern visited by Renaissance writers such as Jan Kochanowski and Mikołaj Rej.

Originally, it brought together students from the Academy of Fine Arts, Jagiellonian University, and the State Theatre School. It quickly evolved into a cabaret, which became a hub of artistic resistance during the Communist era (PRL).

Its first artistic director and the soul of the venue was Piotr Skrzynecki — a colorful, charismatic figure often referred to as the “last Gypsy” of Kraków’s bohemia.

After Skrzynecki’s death in 1997, the cabaret changed leadership but was never shut down — it continues to operate to this day, thanks to the Association of Friends of Piwnica pod Baranami.

Jesuit Residence

Right next to St. Mary’s Basilica, in the southeastern corner of Kraków’s Main Market Square, stands the former Jesuit convent, now known as the Jesuit Profess House or simply the Jesuit Townhouse. It is a lesser-known but fascinating site with a rich history, which for centuries played an important role in the city’s spiritual and educational life.

The Profess House was the residence of Jesuits who had taken their solemn vows — the so-called “Profess of the Fourth Vow.” The building was created in the 17th century by merging and adapting several Gothic townhouses. It had a cloistered character — featuring an inner courtyard, a refectory, a chapel, and monks’ cells. The Jesuits conducted retreats there, as well as scholarly and pastoral work.

Cycling route to Tyniec

A historic Benedictine monastery located south of Kraków's city center, in the Dębniki district.